At 2,602 feet, Mt. Everett is the second-tallest mountain in Massachusetts, behind 3,489-foot Mt. Greylock. To be fair, the two are part of different geologic formations, with Greylock astride the Taconic and Everett sitting at the tip of the Berkshires, separated by a wide valley. With the exception of Everett, the tallest five in the state are all clustered around Mt. Greylock. Everett is designated as SOTA W1/MB-002.

Attached to Mt. Everett to the south by a short saddle is Mt. Race, the ninth-tallest Massachusetts peak, sitting at 2,365 feet. It isn’t a SOTA reference because of that saddle. The two peaks nestle up to each other, the summits only two miles apart, and the saddle between them means that the summit of Race is only 453 feet above the average surrounding terrain, a measurement know as the mountain’s prominence. Mt. Everett boasts a prominence of just over 1,600 feet, qualifying for a SOTA designation.

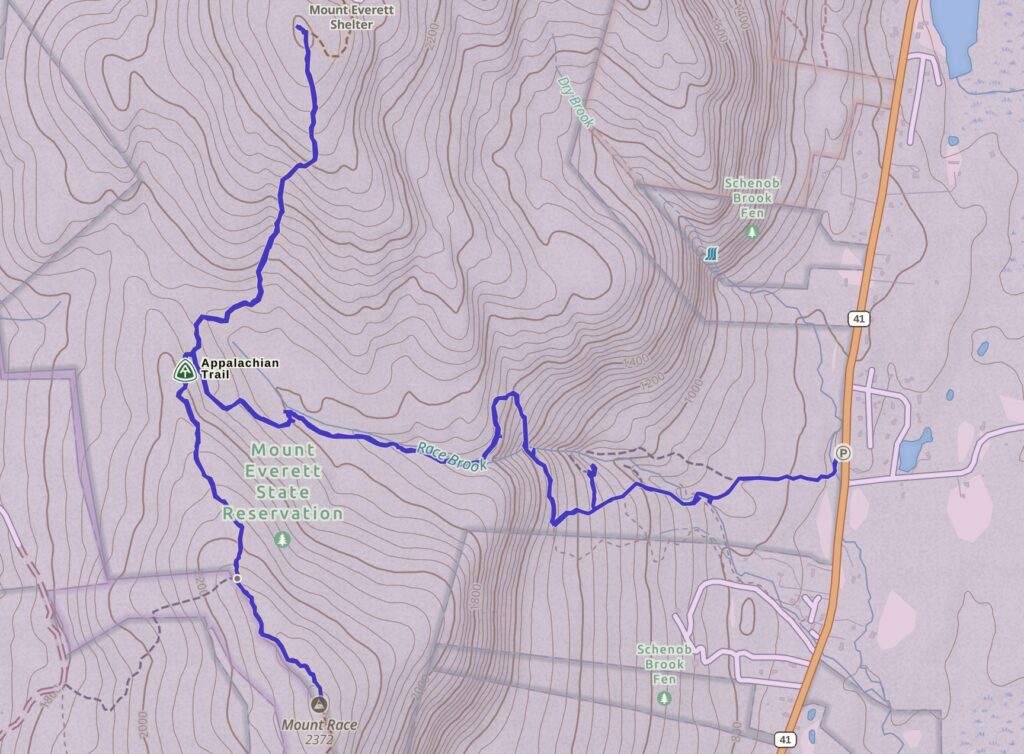

The hike to Everett’s summit is steep in places — I found myself more than once standing for a few minutes in front of a rock face thinking about where each foot and finger would go — but very approachable for hikers in fair or better shape. Parking for this route along the Appalachian Trail is on Rte 41 on the east side of the State Reserve, on the right of the map.

As you can see the trail is T-shaped. The leg of the T follows Race Brook up a fairly steep incline, but you are saved from having to climb straight up the hill by a thoughtful side loop to the north. At the top you can go left to Mt. Race or right to Mt. Everett. Since I was doing a SOTA activation I decided to summit Everett first, since Race isn’t a SOTA reference, and then to visit the other peak if there was time. Each of the three legs is about two miles, so doing both peaks is an 8-mile hike in total.

Every hike has its own character. Here at Everett on this part of the AT the vibe was water, as the trail winds up along Race Brook. It’s steep, and the stream cascades over several significant falls. The vegetation is lush and the forest quiet.

My visit was in late September, and the weather had been dry for quite a bit of the summer, so the falls were more of a trickle than a rush in most spots. I made a note to hike this trail again in the spring to better appreciate the brook. Still, the lowered water level allows you to get out into the stream and really take a good look. The photo above is a really great example of geology happening right in front of you! This waterfall is around 80 feet tall. At the top you can see a narrow channel where water flows out and down along the stream.

See how the top is cut in by the falls? Those rocks are mainly metamorphic and fracture into large blocks. The waterfall erodes the rock along the channel at its top edge, undercutting and weakening the stone. In winter, water seeps into the cracks and freezes. At some point gravity wins and a large section will break off and fall to the bottom of the falls. That’s where all the boulders at the bottom of the photo came from, they were at the top of the falls before it moved upstream. You can trace the fall’s “footprints” as circular pools in the stream…those pools are drop pools, and it is where the falls used to dump water onto the rock below, eroding it. I was able to ‘track’ the stream uphill for several very large steps by looking for old drop pools. Generally I’d see a pool, then boulders, then a pool, and so on.

At the top of the falls I found several large chunks of chlorite in the boulder field. These rocks were part of the original seabed of this area from more than 600 million years ago, forced upward as the crust crumpled and erupted during the Taconic orogeny some 450 million years ago that formed the initial Berkshire mountain range. I held a piece of that rock — some of the oldest you’ll find — and marveled at how it had come to be in my hand. Thinking about and understanding how the landscape around me was formed is one of the best parts of POTA for me.

There are quite a few places to camp along this part of the Appalachian Trail, and they are well-marked, both by trail signs and by an information kiosk at the trailhead by the road. That kiosk also holds a sign-in book for AT hikers. All of the camp sites I looked at were basic raised platforms with a nearby bear locker. Two had primitive toilet facilities (they are called a privy on the trail). The platforms are large enough to hold a six-person tent. I ran into three groups of hikers, and chatted a bit each time. All of the groups were spending “two or three or four” days on the trail. One pair of old geezers I met at the top of Everett were headed to Bear Mountain in New York. One of the geezers laughed and said that he and his companion had often done the hike when they were young, working their way out to Bear and then practically running back over the course of several days. Now, he said, they just leave a car at both ends. I hear you, fellow geezer!

It took me around three hours to climb just over two miles to the junction at the top of the T. My reward? Another stiff climb to get to Everett’s summit. Fortunately the trail maintainers (bless each of you!) lent a hand with strategically placed steps, some bolted directly into the rock face. Whenever I see this level of effort deep in the woods, I know there’s a campsite nearby! And I did appreciate those helping steps. Ain’t gonna lie, it’s a steep climb.

There’s not all that much happening at the summit. The view at the top of this article is from roughly half a mile down from the summit, which itself is somewhat flat. In the 1800s the hill was called The Dome of the Taconics and Bald Mountain. There’s been a fire tower up at the top at various times since 1912, with the last being dismantled around 2002.

I brought the KX2 and my trusty 17′ whip along for this activation. I say ‘trusty’ but that wasn’t always the case! I pair the whip with the Gabil GRA-ULT01 MK3 tripod. I love that tripod — they aren’t cheap, around $140 right now on Amazon, but they are crazy sturdy and it folds down into a tiny package. I use four 32′ radials that are fashioned from BNTECHGO 26 AWG silicone-wrapped stranded wire. The stuff has the consistency of cooked spaghetti but it can be wound around your fingers and will unwind without a tangle, every time.

What was happening with this setup was that the SWR was all over the place. I’d hit the tuner on the KX2, which is famous for matching nearly anything, and then in the middle of a QSO the rig would limit power, or just shut down altogether with HI CURR and the SWR would be crazy high. I thought it was the whip, then the cable, the radials and even the tripod, since the KX2 had no trouble whatsoever when I used my EFHW wire.

The clue came finally on one outing where I was trying to get the rig to match the vertical, and I picked up the coax to move it out of the way. The SWR instantly dropped to 1.1:1 and stayed that way, as long as I held the coax. Aha! Common-mode current was ruining my day. I bought a Palomar JC-1-1500-3 inline choke (about $25), and the next time I was in the field added it to the feed at the base of the vertical. Instant gratification — I’ve had the antenna out now on half a dozen activations with zero matching problems. As an aside, I installed a second choke at the feed of the EFLW (82′) at the shack, and the noise level on 40m dropped from S7 to S0. I couldn’t use 40m before, and now I can, it’s like having a new radio.

I set up the vertical with the feed directly over the USGS survey marker at the peak. That’s required to get full SOTA points, right? I’ve also gotten into a habit of attaching Tibetan prayer flags to the top of my vertical. I figure that any little bit helps.

As I was finishing setup I heard a voice from a bit lower on the trail exclaim, “Hey, I haven’t seen flags since I was in Nepal!” We had a nice chat when he reached the top with his hiking partner.

The activation was really pleasant. Unlike the past few outings, the bands were in good shape and it took about 30 minutes to log 20 QSOs, including with my friends Bob WC1N and Ken NS1C who were doing one of their famous dual-CW operations on 40m. They pass the key back and forth, just like the SSB ops pass the mic. I think they’ve had as many as five operators participating at some parks. I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to reach them in the middle of the day on that band, but they were loud and clear, and I stuck around on 40 for a few more QSOs before packing up and heading to my second summit of the day.

Mt. Race got the shaft. It is legitimately the ninth-tallest mountain in Massachusetts, snuggled up close to Mt. Everett and connected to it by a saddle that is itself quite high, giving the summit of Mt. Race a prominence — its height above average surrounding terrain — of just over 450 feet. It’s not a SOTA reference, in other words.

This is a pity, because the summit is just as tough as Everett’s to get to, and in fact Mt. Race has the better views.

To get to Race’s summit from Everett, just walk across the top of the T on the map. It’s just over two miles, and you did all of the hard climbing to get to the top of Everett, which is something I thanked myself for. If I’d done Race first, I’d still need to walk two miles uphill most of the way to the other peak.

The two miles to Race gives you a good chance to observe the plants along the trail. On the climb up the leg of the T you are mainly in pine and relatively young hardwood forest, under canopy for the most part. On the AT along Race Brook you are walking through a stream ecology, so you’ll see mosses and ferns in addition to black huckleberry and mountain laurels. Up top, though, along the arms of the T, you’ll find plants more similar to higher terrain. There are blueberry and huckleberry bushes, small ones, and now you are in a scrub oak / pitch pine section that is more windswept and arid. It’s also more open, and it is the summit of Race, not the taller Everett, where you’ll get that 360º view.

If you put your foot on the hole where the survey marker for Mt. Race used to be and look back the way you came, you’ll see Mt. Everett, two miles distant, on the other end of the T.

I spent just over 8 hours on the mountain. The descent was 90 minutes of that, a steep but relatively simple retrace of my steps. I took two trekking poles with me for the descent, but left them strapped to the pack as I found it easier to work with my hands than with poles in the tough parts. Poles are always a hard decision for me — my pack loads out at 32 pounds for a typical all-day hike that includes an activation, and humping that weight up and down the side of big hills at my advanced age is both a blessing — it keeps me in shape — and a curse — at 8 miles it starts to feel heavy. I took the poles because I saw the terrain on the topo map and wanted to be able to descend safely, especially in the areas adjacent to water. It turns out I didn’t need them, but I’d take them again in the same situation. Socks, too, I always have a spare pair of dry socks in the pack. Honestly, with good gear properly fitted, the weight is hardly noticeable.

I’ll give a shout out to the Holiday Inn Oak ‘n’ Spruce Resort in Lee MA where I stayed for both this trip and a trip back in March to Mt. Wilcox. It’s a time-share condo sort of situation, but individual units are available on Priceline for just over $80 per night in their off-season. The property abuts US-4711 Beartown State Forest and Mt. Wilcox, you can literally roll out of bed and walk over to the trailhead.

I’d like to see the trail up Everett in the spring when the waterfalls are gushing. Some of them are quite high, and it’ll be a completely different vibe and will require a different plan. It might be fun to retrace Thoreau’s steps from Guilder Pond to the summit, a walk he did in 1844. Like Mt. Tom in Holyoke, there’s something unique about this place and I’d like to experience it through several different seasons.