I did something at Big River WMA in West Greenwich, Rhode Island, that I very rarely do these days: I wandered. I entered the WMA on the east side, along Hopkins Hill Road at Tarbox Pond. This was due to another first, at least recently: A filled parking lot, a big one, with room for 15 vehicles or so. I should not have been surprised, it was one of those beautiful end-of-summer weekends that we enjoy here in New England, with sunny skies and temperatures in the low 80s. Everyone and their dog was out walking, and good for them! Winter will be here soon enough and we’ll be huddled around the little fires we build in our living rooms.

But not this day! My wife was busy winning ribbons at the New England Dahlia Society’s annual show at nearby Tower Hill Botanical Gardens, and I headed for the hills, so to speak. Big River is big, over 8,000 acres, and is the largest undeveloped chunk of land in Rhode Island, which itself is not all that large. It encompasses an area that has been under human use for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, and its size provides several distinct habitats, from marshy ponds to rocky highlands.

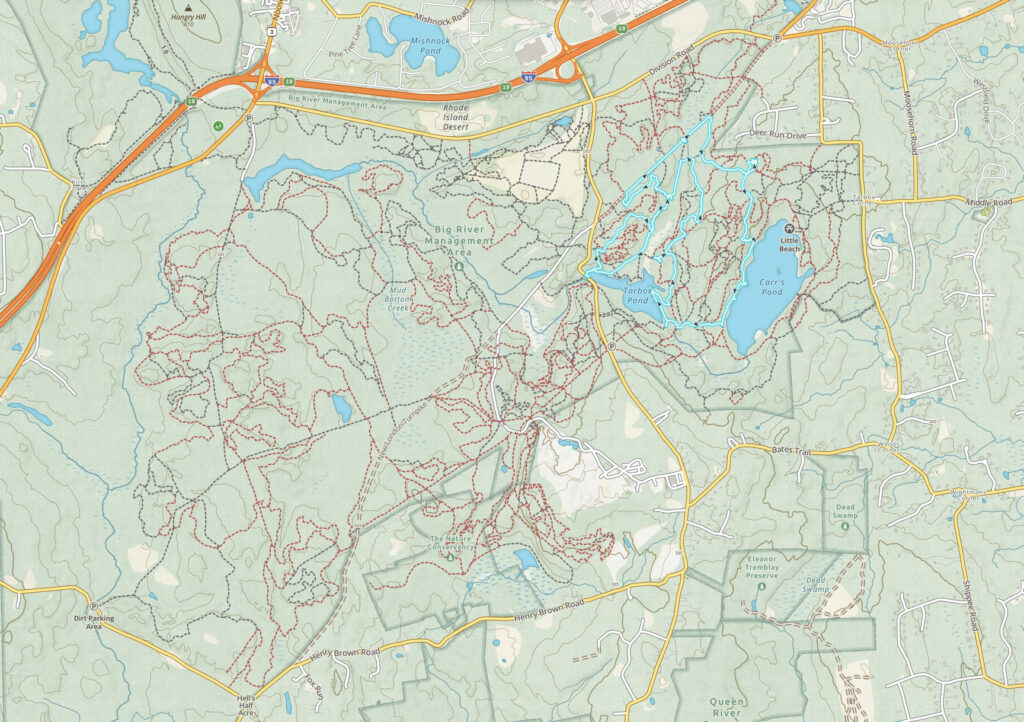

The map is zoomed out far enough that the crazy web of trails that criss-cross the park isn’t visible. Big River is a magnet for dirt bikes, and the RI NEMBA (New England Mountain Bike Association) spends a lot of time and effort out here to maintain hundreds of tiny trails. I quickly realized that it wasn’t going to be possible to check the map at every intersection because I could practically see the next intersection from the one I was standing in. Instead, I took a look at the terrain on the topo map, decided roughly where I wanted to activate from, noted where the sun was in that direction, and then just hiked, keeping the sun in more or less the right spot.

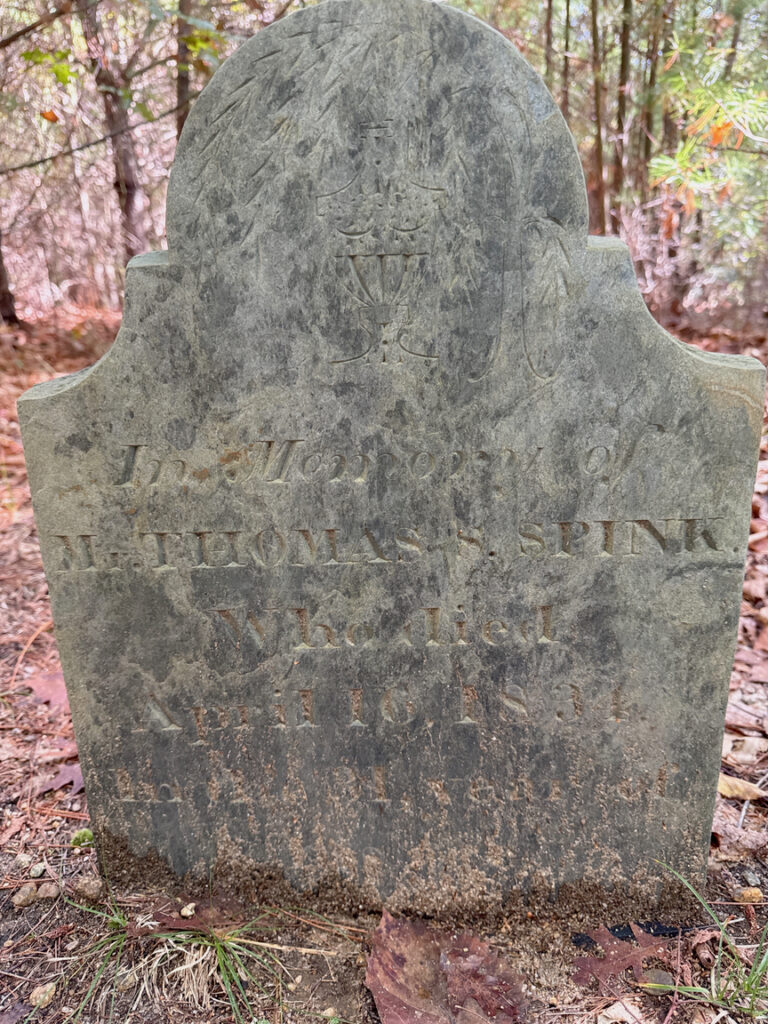

I’d parked in a cut along Hopkins Hill Road, from that spot a wide path led into the woods. Almost immediately there was evidence of human habitation — a tiny, ten-stone burial area on a small rise near Tarbox Pond.

This is the Thomas Spink plot. Thomas died young in 1834 at just 30, and his stone is the only one that has visible markings — it is made of slate, traditional at the time and readily quarried in the area. His stone had been removed by the 1970s according to contemporary reports, but it was returned in 2006 by a gentleman who had come into possession of the marker but didn’t know where it belonged. The nine other markers are smaller and made of granite, quarried not far away. They are heavily eroded and no engravings are visible on any of them.

The pond is lovely, a typical New England mill pond. The land for Big River WMA was originally set aside in the late 1950s to build a large drinking water reservoir for the state. Over about ten years, 200 families were displaced as their land was claimed by eminent domain laws, and engineering plans were developed. By 1970 work was underway, with quarrying taking place to provide granite structures, clearing for dams and outbuildings, and construction of test dams and spillways. In the 1990s the Environmental Protection Agency sued the state to halt developemnt, citing the destruction and inundation of a significant portion of Rhode Island’s wetlands. The project was abandoned and the property transferred to the RI department that handles parks and WMAs.

Because of the history, there’s still a lot of evidence of human use in the park. Quarrying is everywhere, from small single-boulder cart pits from the 1800s up to large-scale granite quarries set up for work on the dams. I’m a rock hound and look for this sort of thing, and I’ll can tell you that if you dropped me in the northeast quad of this park and asked me what I was looking at, I’d tell you I was in a quarry.

That’s not the entire story, of course. This was farm and pasture land during colonial times, and an ancestral home to the Nipmuc tribes who were being pushed by European settlers away from their traditional coastal homes. As I wandered near Carr’s Pond I ran across a low burial mound, oriented due north-south, along with a serpent effigy in stone that stretched about 15 feet along the ground, with its head a shallow water basin. This is classic Nipmuc architecture and I now look for it when I’m in an area with a marshy pond and a low hill on the banks.

Above are three structure that I ran into on the trail. The brick building looked to be part of a rail system, either a through line or one built specifically to haul granite from the quarries to the construction site. The shelter in the center was deeper in the woods and likely in use as a hunting shack, all you need is a tarp across the top in case of rain. The house foundation on the right looked to be from the early 1900s.

Even before the Nipmuc lived here, humans have been attracted to the streams and proximity to the ocean. Archaeological surveys conducted during the 1970s condemnation studies recorded multiple prehistoric sites along the river terraces — stone flakes, hearths, and small village scatters dating back 2,000–3,000 years. The high terraces and knolls near Carr’s Pond and Tarbox Pond were favored for seasonal encampments and food processing.

Wandering has a lot of benefits! I wasn’t constantly fiddling with my map, and so I was more attentive to what was around me. My general approach was to keep the sun more or less in front of me and to the left, and to head uphill. That worked well, and I spent the next few hours looking and listening. A Pileated Woodpecker was curious about me and paced me for a mile, keeping just far enough away that I could hear him but see him. A trio of Barred Owls were having a lively conversation about something — me? — as I passed along a small stream.

After about three hours I’d worked myself over to a high spot that looked like a good place to operate from. “High” is relative, this area of the park tops out at around 500 feet. A big granite boulder had split in some past aeon, and it provided for a nice little table and chair to set the station up on.

I don’t know why, but I ended up mainly hunting on this activation. Out of 19 QSOs, 13 were Park-to-Park, and I also logged two SOTA operators. It was very leisurely and I hopped from band to band following the spots. Conditions were good and I was able to make contacts on five bands. The KX2 doesn’t have 6m capabilities but I have a hunch I could have made a few Qs on 50MHz if I’d brought a different radio. I normally pick a frequency, spot, and just sit and call CQ. This was a nice change of pace and I’ll start working more hunting into my routine.

I’ve been carrying a 17-foot collapsible whip pretty much exclusively these days. For quite a bit of the summer I hauled two complete antennas in the pack, the vertical along with its tripod and radials, and also an EFHW cut for 40m and all its ropes and weights and wire. The vertical was really fussy, it’d be fine for a bit and then mid-QSO decide that it wasn’t going to match any more, and the KX2 would respond by dropping my output power to just a few watts. I was constantly futzing with the thing and it got to the point where I didn’t trust it, hence the EFHW.

I realized what the problem was on one outing when the vertical was refusing to match and I picked up the coax to move it. The SWR dropped instantly to 1:1 and stayed there as long as I had the coax in my hand. Common-mode current was all over that line, and I was acting as a choke. I finished the activation with the feedline draped across my leg, also an excellent choke, and when I got home ordered Palomar Engineering inline chokes, one for POTA and one for the EFLW at the QTH. That fixed it, the vertical is rock solid, matches everywhere, and I don’t have to wind myself in coax.

Walking back was a bit easier, I decided to aim for Carr’s Pond, which was occasionally visible through the trees, and walk along the shore toward the parking area. This avoided quite a bit of the cobweb of trails, and it brought me into one of the larger commercial quarries that had produced granite structure for the dams and associated buildings. There are quite a few test pits in the woods, but this was a blast-the-cliff-face-off kind of quarry.

It was a big operation, but you can see that they’d just started when work was halted — there’s quite a bit of prep work here in terms of infrastructure and blasting, but nearly no dressed stone, only raw chunks. It’s possible that the stone was hauled somewhere for finishing, but I didn’t see any evidence of that kind of operation. I’m a little surprised that no one has worked a deal with the state to exploit this material, it’s already in chunks and the granite is gorgeous, it would look really lovely polished.

Just a reminder that late summer / early fall is mushrooming season in New England. These sulphurs in the photo below were not far from parking. Unfortunately they were just a bit old to eat, but I’d pulled a nice batch from US-8383 Wrentham State Forest a few days before, so we were flush with mushrooms.

I spent six hours and walked a little over six miles in Big River, and as you can see from the map traversed only a small part of the WMA. It’s just really huge. The hiking was spectacular, and it’s a great place to activate from, either hiking in or setting up in one of the many parking areas that ring the park. There’s even a beach on Carr’s Pond, and some small islands if you’d like to paddle out to your site. There’s no camping available here, but a few nearby campsites can accommodate you, including a backpacking area in Acadia WMA.

I felt comfortable in Big River. The folks I ran into were friendly, and their little dogs, too. The trails are well-maintained and not rugged at all, even if they wind crazily through the park. There’s a lot of parking, and the place is big enough to offer several different experiences depending on your mood. It is on my short list of parks that I want to spend more time in.