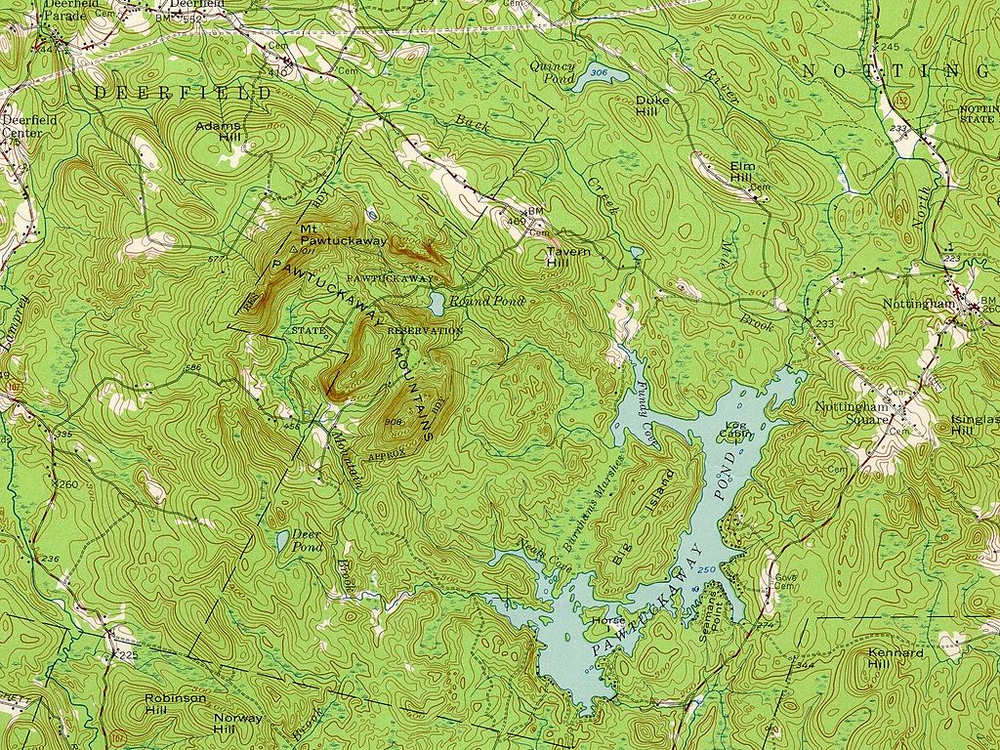

Take a look at the topo map below. If someone were to put this on the desk in front of you and ask you to describe the central feature, what would you say? My first thought was that it’s an impact crater…the circular structure is obvious, a raised rim around a central depression, and it even has a ‘knob’ in the middle that you often see in impact craters. The Pawtuckaway ring is roughly 1.5 miles in diameter, slightly larger but not significantly so than the famous Meteor Crater in Arizona.

My second choice would be the remnants of a volcanic eruption, for mostly the same reasons — the circular structure sure looks like a blown out caldera, but the size is off, typical North American calderas can be 15 to 20 miles wide. In either case the low slump of the crater walls at Pawtuckaway would lead me think it was quite old due to erosion.

Neither guess is correct, and it turns out that Pawtuckaway has a much more interesting backstory. Around 200 million years ago, the tectonic plates in the region were being pulled apart to form what would become the Atlantic ocean. The intense energy created by this process melted deep rock, and magma began to intrude underneath the primarily metamorphic schists in the bedrock. The magma ate away at the roof of this large underground chamber, pushing into cracks, cooling and contracting, breaking it apart, causing the area above it to sink down.

As the body of magma cooled, it contracted and cracked in roughly circular concentric vertical patterns, a lot like a cake layer might when you pull it from the oven and let it cool, and regional stresses helped open the cracks up. At least two more intrusive magma pulses happened after this, spread over millions of years. As the magma built up underneath during a surge, it was forced up into the vertical cracks in the schist, creating dyke walls. Imagine a jelly roll on its side. This kind of structure is called a ring dyke by geologists.

The syenite and monzonite making up these later flows is harder relative to the original sedimentary / metamorphic schists. The metamorphic rock starts as sediment on the bottom of a body of water and is heated and compressed over geologic time into a solid mass, but the syenite / monzonite complex is igneous, and has a crystalline structure. Because it is harder, over time the schist weathered away, leaving the circular walls of the crater. The depressed area in the center ended up being lower than the surrounding terrain, and became dotted with marshes and small ponds. Note that the large lake, Pawtuckaway Pond, to the east is not part of this geology, but is the result of a pre-Colonial era dam.

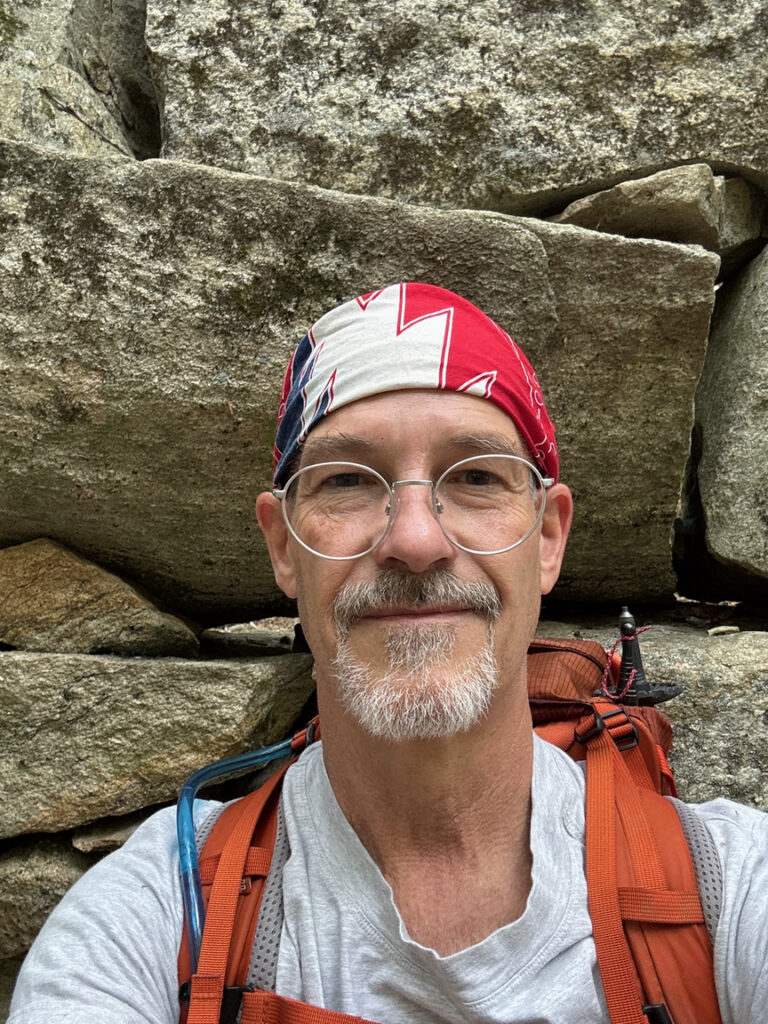

I’ve lived in New England for some thirty years, and I love geology and maps — I have no idea why I’d never seen this large feature before. I even lived in New Hampshire, near Mt. Monadnock, for a few years and hiked it quite a bit…why didn’t I look just a few miles east? In any event, once I saw the structure on the map I knew I’d be heading there for my next POTA activation.

Apart from the geology, Pawtuckaway State Park is a very popular destination for hiking, winter sports like cross-country skiing and snowmobiling, and is home to Pawtuckaway Lake with miles of fishing, beaches, and other water activities. I found a camping spot on Horse Island on the southeastern shore, one with a nice view of the lake.

The campsites on Horse Island are $40 per night in 2025 and are well-maintained and quiet. This part of the island has a new facility that includes showers, restrooms, and kitchen sinks. There’s a camp store about a mile from the spot. I really like camping at POTA sites, not only do I get an early start on what are often long and challenging hikes, but in the evening I can set up a little campfire and the KX2 and get a late-shift activation in. An added bonus is being able to relax in the hammock after a solid day hiking and watch the sun go down. The only downside is that the loons wake up around 5am on the lake and apparently have a lot of things to discuss with their friends, shouting at each other across the water,

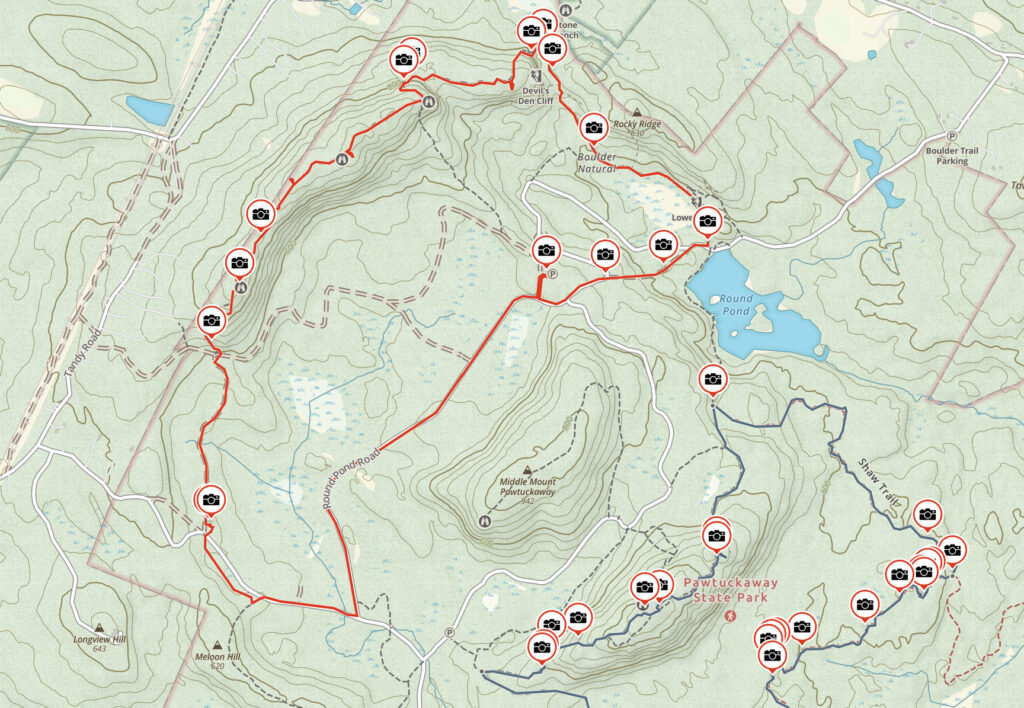

I decided to approach Pawtuckaway in two hikes over two days. On the first day I focused on the southern crater, which was not at all close to my campsite, but I decided to hike to it nonetheless. The weather was on-and-off rain showers, but mild, and I decided to leave the radio behind and do my activation the following day. The decision was easier to make in that the northern rim is a SOTA site, and the southern one isn’t. I’m something of a ‘casual’ SOTA enthusiast, really I only do SOTA if I’m already standing in a POTA reference.

Most of the hike to the south rim from Horse Island is in a relatively young hardwood forest mixed with typical New Hampshire pine stands. Early settlers tried their best (and more or less failed) to tame the rocky land, and you’ll find quite a few walls and foundations scattered around the park, many from the late 1600s. The trails are very well maintained and had more blazes per mile than I’d ever seen in a park…a welcome change from hiking in California, where I didn’t see a single blaze in over a week of hikes.

There are some fairly large boulders on this side of the crater, often 30 to 40 feet high, and I took a lot of photos of them, spent some time poking around and under some of them, and thought about what it might have looked like when the trees were young or not there at all. Pawtuckaway is world-famous for its Boulder Field, and I thought this was it.

Narrator: This wasn’t it.

There are also some very large birds in the woods here, I’m guessing that these were pecked out by a pileated woodpecker…

After a steep climb, you’re up on the rim of the dyke. This side is pretty gentle and you pop in and out of the treeline at regular intervals. The big feature on South Mount is a lookout tower from which you can get an overview of the crater structure and also watch hawks drift by as they play in the thermals along the ridge. You can drive right up to the tower if you don’t want to hike to it, which I only realized when a family of four, including two small kids, popped out of the trees just below where I was standing…they did not at all look like they were or even should have been hiking, and then I saw the trail to the parking lot just below.

Someone has studded the tower with bird feeders — seed and hummingbird mix — and boy, did the birds seem to appreciate that!

I was happy to do the hike without radios. When I’m loaded out for a POTA hike, the pack weighs roughly 32 pounds and is a bit bulky. When I leave the rig behind it really lightens the load and I can concentrate more on the hike. The southern hike was timed perfectly, by the time I’d come out of the trees and up onto the rim the rain had stopped, and I was able to have a bite of lunch with spectacular views.

On the following day, after a disappointing breakfast of dehydrated eggs and sausage, I headed over to the park headquarters to ask about approaches to the north rim. Apparently it’s a common question as the ranger pulled out a printed set of directions. I had to leave the park and drive around the perimeter, nearly 12 miles, to pick up Reservation Road, and then Round Pond Road up to a parking area, roughly in the middle of the map below at the ‘P’ symbol.

I hiked counterclockwise on the trail, first visiting the world-famous Boulder Field. Now, I have to admit that I was a little naive about this feature. I’d read that the park had an amazing Boulder Field that rock climbers from around the world visited to see and climb rocks the size of which you aren’t going to find in many other places around here. Many are named and graded for difficulty, and groups come here to practice various climbing techniques. I was convinced that I’d come across something like an art gallery in a large, open field, with each boulder clearly marked with its name, difficulty, common routes up, and so on,

Aye, yi, yi. What it really is is a boulder field, as in “a field of debris”. And how those boulders got to be be in that field of debris is another fascinating Pawtuckaway story.

Take a look at the map again. About 50,000 years ago, very recent in geological time, the Wisconsin glaciation, part of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, moved slowly and inexorably from north to south across this landscape. The ice was a mile thick in places. It hit the north side of the crater first and embedded the crater. The ice stuck around for about 25,000 years.

The rock that makes up the crater walls, mainly syenite and monzonite, forms with perpendicular fracture lines. Big ones. The weight of a mile of ice added additional stresses, and so did freeze-thaw cycles as water seeped into deep cracks and expanded as it refroze. The glacier itself was not stationary, it moved slowly, northwest to southeast, snapping off chunks of the top of the crater and transporting them to the south. The crater was under ice for tens of thousands of years.

As the glacier melted, from about 17,000 years ago, rock that was embedded just fell. At Pawtuckaway the massive pieces of the crater that the glacier had snapped off didn’t go very far, and you’ll find most of it in the bowl to the east of the peak, deposited as building-sized boulders. Because the rock itself has perpendicular fracture lines, the chunks tend to be rectangular, and often they fell in such a way as to create ‘rooms’ and ‘houses’ of stone. Here’s a picture of part of Devil’s Cliff that was snapped vertically — it doesn’t really show scale well, I could crouch in the smaller cave on the left. The cliff itself rises nearly straight up for 120 feet or more and is what geologists would call a ‘pluck scar’.

It wasn’t too far from the cliff that I found a beautiful fist-sized chunk of jaspered quartz, itself carried south by the glacier and dropped where I would discover it some 15,000 years later. had an Algonquin spotted it first, it would have been made into prized scrapers and points.

The north rim is slightly higher than the other two, and the south rim is slightly higher than the middle one. Climbing up the lookout tower on South Mount is one way to see the whole structure, but you can also find spots on North Mount where you can look across the bowl and see both of the other rims. They’re close enough that the circular structure is obvious — another ring dyke not far away in Ossipee NH (near Lake Winnipesaukee) is over 15 miles in diameter and its walls drop below the horizon, but here you can see the curve of the walls.

I popped out of the trees on North Mount at one point and was really confused by what I saw (below):

What was the tower doing there on top of Middle Mount? It is firmly attached to the top of South Mount, I’d just been there the day before. I had found a spot here on North where the angle is such that Middle Mount blocks the very top of the ridge of South Mount, so in the picture you are seeing Middle Mount and then the tower on South, on the rim behind it. As I walked downhill along the path I could see the top of the tower sinking below the ridge of South Mount. It was an excellent geometry lesson!

I found the northern rim to be more interesting than the southern. It’s more exposed, and the views both across the bowl and also beyond to the surrounding mountains are just lovely. On the southern rims you are mostly below the treeline with the occasional view. It was a shorter hike since I’d parked near the hill, just under 6 miles.

The North Mount of Pawtuckaway is a SOTA reference, W1/NL-019, and I’d decided to do my activation from there to cover both SOTA and POTA. I found a little meadow near an overlook and set up the EFHW and KX2 and had a bit of lunch and a short but fun activation. It was good to see some POTA friends pop in, like Ken NS1C, and poor Mario IK1LBL, he hunts me a lot, and every single time it takes me three or four attempts to get his callsign right, I just have a mental block around sending L-B-L, way too many dits in there!

I’m really enjoying this kind of POTA operation, where I am camping / hiking in some beautiful space, doing an activation or two on the side. It’s more relaxing than my typical outing where POTA is a focus and I hike in, activate, and hike out. I guess it’s a subtle difference. Waking up and being able to get immediately on the trail is key for some of my longer hikes.

On the west side of North Mount, around the foot of Longview Hill, I ran into the foundations of a very large house. Early settlers, late 1600s to mid 1700s, really struggled around here to find enough dirt to support crops or livestock. It’s just way too rocky, and as the westward expansion took hold, a significant number of these settlers abandoned their farmsteads and headed west. As a result you’ll see quite a few very old stone structures in the park, and not a lot after that. It’s the same with the trees, you’ll see some pretty big hardwoods near a part of a stone wall, for example — those were ‘meadow’ trees that stood more or less alone out in a field, or near a wall, and they didn’t hav any competition, so they were able to grow and block the sunlight such that other trees had trouble taking root. None of the hardwoods are that old, and you can see where the fields had been cleared and mainly pines started to move in over the past 100 years or so.

This is another case where a photo doesn’t give a sense of scale. These stones are really, really large…

Below is a shot of a corner in the structure showing what might be the most interesting feature. Take a look at the stones on the left, toward the bottom. You can see marks typical of a plug-and-feather style of quarrying, where you drill a hole in the stone, put thin metal shims (feathers) into the hole, and then a wooden or metal rod (the plug). You’d pound the plugs in sequence along the rock, and the pressure would force the rock apart on its natural fracture lines. Sometimes a wood plug would be inserted and water poured over it to get it to expand and crack the stone. At Pawtuckaway the rock, mainly syenite, fractures orthogonally, with big natural cracks at right angles, just perfect if you want large blocks to build with.

That’s on the left. Look at the other stones, see any evidence of plug-and-feather quarrying? I didn’t, and I looked pretty hard. These stones weren’t quarried, they were harvested off of the surrounding land. The glaciation that led to the Boulder Field dropped big chunks of crater all over the area, and they just happen to stack up very nicely, with maybe a bit of trimming here and there to get it just right.

I’m not certain that this structure was ever finished. It isn’t intact, and the foundation doesn’t run all the way around. I’d normally see some sort of hearth, but not here, and I don’t think it was a barn because of the footprint. There’s a creek nearby, so maybe it was supposed to be a storage area for milled grain, though again I didn’t see any evidence of a wheel on the creek.

My guess is that it was started and abandoned along with the other homesteads in the area. The Algonquin tried to tell the settlers that it wasn’t a good place to farm, but apparently they needed to find out the hard way.

One Response

Fantastic read again Perry, as always. I would love to live where you are!